Background Information

First, let’s have a look at some common, practical questions that people have when trying to choose the right Java version for their project.

If you want to learn more about a specific version, go to the AdoptOpenJDK site, choose the latest Java version, download, and install it. Then come back to this guide to and still learn a thing or two about different Java versions.

What Java Version Should I Use?

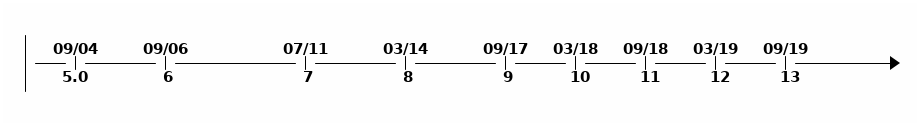

As of September 2019, Java 13 is the latest released Java version, with newer versions following every 6 months — Java 14 is scheduled for March 2020, Java 15 for September 2020, and so on. In the past, Java release cycles were much longer, up to 3-5 years!.

With that many new versions coming out, there are basically these real-world usage scenarios:

- Legacy projects in companies are often stuck using Java 8 (see the “Why Are Companies Still Stuck On Java 8?” section below). Thus, you will be forced to use Java 8 as well.

- Some legacy projects are even stuck on Java 1.5 (released 2004) or 1.6 (released 2006) — sorry, pals!

- If you are making sure to use the very latest IDEs, frameworks, and build tools and starting a greenfield project, you can, without hesitation, use Java 11 (LTS) or even the latest Java 13.

- There’s the special field of Android development where the Java version is basically stuck at Java 7, with a specific set of Java 8 features available. Or, you can switch to using the Kotlin programming language.

Why Are Companies Still Stuck on Java 8?

There’s a mix of different reasons companies are still stuck with Java 8. To name a few:

- Build tools (Maven, Gradle, etc.) and some libraries initially had bugs with versions Java versions > 8 and needed updates. Even today, with e.g. Java 9+, certain build tools print out “reflective access”-warnings when building Java projects, which simply “feels not ready”, even though the builds are fine.

- Up until Java 8, you were pretty much using Oracle’s JDK builds and you did not have to care about licensing. Oracle changed the licensing scheme in 2019, though, which caused the Internet to go crazy saying “Java is not free anymore” — and a fair amount of confusion followed. This is, however, not really an issue, which you’ll learn about in the “Java Distributions” section of this guide.

- Some companies have policies to only use LTS versions and rely on their OS vendors to provide them these builds, which takes time.

To sum things up, you have a mix of practical issues (upgrading your tools, libraries, frameworks) and political issues.

Why Are Some Java Versions Called 1.X?

Java versions before 9 simply had a different naming scheme. So, Java 8 can also be called 1.8, Java 5 can be called 1.5, etc. When you issued the java -version command with these versions, you got an output like this:

1c:\Program Files\Java\jdk1.8.0_191\bin>java -version

2java version “1.8.0_191” (1)

3Java(TM) SE Runtime Environment (build 1.8.0_191-b12)

4Java HotSpot(TM) 64-Bit Server VM (build 25.191-b12, mixed mode)

This simply means Java 8. With the switch to time-based releases with Java 9, the naming scheme also changed, and Java versions aren’t prefixed with 1.x anymore. Now, the version number looks like this:

1c:\Program Files\Java\jdk11\bin>java -version

2openjdk version “11” 2018-09-25 (1)

3OpenJDK Runtime Environment 18.9 (build 11+28)

4OpenJDK 64-Bit Server VM 18.9 (build 11+28, mixed mode)

What Is the Difference Between Java Versions? Should I Learn a Specific One?

Coming from other programming languages with major breakages between releases, like say Python 2 to 3, you might be wondering if the same applies to Java.

Java is special in this regard, as it is extremely backwards compatible. This means that your Java 5 or 8 program is guaranteed to run with a Java 8-13 Virtual Machine — with a few exceptions you don’t need to worry about for now.

It obviously does not work the other way around, say your program relies on Java 13 features that are simply not available under a Java 8 JVM.

This means a couple of things:

- You do not just “learn” a specific Java version, like Java 12.

- Rather, you’ll get a good foundation in all language features up until Java 8.

- And then, you can learn, from a guide like this, what additional features came in Java 9-13 and use them whenever you can.

What Are Examples of These New Features Between Java Versions?

Have a look at the “Java Features 8-13” section below.

But as a rule of thumb: The older, longer release-cycles (3-5 years, up until Java 8) meant a lot of new features per release.

The six-month release cycle means fewer features per release, so you can catch up quickly on Java 9-13 language features.

What Is the Difference Between a JRE and a JDK?

Up until now, we have only been talking about “Java.” But what is Java exactly?

First, you need to differentiate between a JRE (Java Runtime Environment) and a JDK (Java Development Kit).

Historically, you downloaded just a JRE if you were only interested in running Java programs. A JRE includes, among other things, the Java Virtual Machine (JVM) and the “java” command-line tool.

To develop new Java programs, you needed to download a JDK. A JDK includes everything the JRE has, as well as the compiler javac and a couple of other tools like javadoc (Java documentation generator) and jdb (Java Debugger).

Now why am I talking in past tense?

Up until Java 8, the Oracle website offered JREs and JDKs as separate downloads — even though the JDK also always included a JRE in a separate folder. With Java 9, that distinction was basically gone, and you are always downloading a JDK. The directory structure of JDKs also changed, with not having an explicit JRE folder anymore.

So, even though some distributions (see the “Java Distributions” section) still offer a separate JRE download, there seems to be the trend of offering just a JDK. Hence, we are going to use Java and JDK interchangeably from now on.

How Do I Install Java or a JDK Then?

Ignore the Java-Docker images, .msi wrappers, or platform-specific packages for the moment. In the end, Java is just a .zip file; nothing more, nothing less.

Therefore, all you need to do to install Java onto your machine is to unzip your jdk-{5-13}.zip file. You don’t even need administrator rights for that.

Your unzipped Java file will look like this:

Directory C:\dev\jdk-11

12.11.2019 19:24 <DIR> .

12.11.2019 19:24 <DIR> ..

12.11.2019 19:23 <DIR> bin

12.11.2019 19:23 <DIR> conf

12.11.2019 19:24 <DIR> include

12.11.2019 19:24 <DIR> jmods

22.08.2018 19:18 <DIR> legal

12.11.2019 19:24 <DIR> lib

12.11.2019 19:23 1.238 releaseThe magic happens in the /bin directory, which under Windows, looks like this:

Directory C:\dev\jdk-11\bin

...

12.11.2019 19:23 272.736 java.exe

...

12.11.2019 19:23 20.832 javac.exe

...So all you need to do is unzip that file and put the /bin directory in your PATH variable, so you can call the ‘java’ command from anywhere.

(In case you are wondering, GUI installers like the one from Oracle or AdoptOpenJDK will do the unzipping and modifying the PATH variable for you, that’s about it.)

To verify you installed Java correctly, you can then simply run java -version. If the output looks like the one below, you are good to go!

openjdk version "11" 2018-09-25

OpenJDK Runtime Environment 18.9 (build 11+28)

OpenJDK 64-Bit Server VM 18.9 (build 11+28, mixed mode)Now, there’s one question left: Where do you get that Java .zip file from? Which brings us to the topic of distributions.

Java Distributions

There’s a variety of sites offering Java (read: JDK) downloads and it is unclear “who offers what and with which licensing”. This section will shed some light on this.

The OpenJDK Project

In terms of Java source code (read: the source code for your JRE/JDK), there is only one living on the OpenJDK project site.

This is just source code, however, not a distributable build (think: your .zip file with the compiled java command for your specific operating system). In theory, you and I could produce a build from that source code, call it, say, MarcoJDK, and start distributing it. But our distribution would lack certification, to be able to legally call ourselves Java SE compatible.

That’s why, in practice, there’s a handful of vendors that actually create these builds, get them certified (see TCK), and then distribute them.

And while vendors cannot, say, remove a method from the String class before producing a new Java build, they can add branding (yay!) or add some other (e.g. CLI) utilities they deem useful. But other than that, the original source code is the same for all Java distributions.

OpenJDK Builds (by Oracle) and OracleJDK Builds

One of the vendors who builds Java from source is Oracle. This leads to two different Java distributions, which can be very confusing at first.

- OpenJDK builds by Oracle(!). These builds are free and unbranded, but Oracle won’t release updates for older versions, say Java 13, as soon as Java 14 comes out.

- OracleJDK, which is a branded, commercial build starting with the license change in 2019. This means it can be used for free during development, but you need to pay Oracle if using it in production. For this, you get longer support, i.e. updates to versions and a telephone number you can call if your JVM goes crazy.

Now, historically (pre-Java 8), there were actual source differences between OpenJDK builds and OracleJDK builds, where you could say that OracleJDK was ‘better’. But as of today, both versions are essentially the same, with minor differences.

It then boils down to you wanting paid, commercial support (a telephone number) for your installed Java version.

AdoptOpenJDK

In 2017, a group of Java User Group members, developers, and vendors (Amazon, Microsoft, Pivotal, Red Hat, and others) started a community called AdoptOpenJDK.

They provide free, rock-solid OpenJDK builds with longer availability/updates and even offer you the choice of two different Java Virtual Machines: HotSpot and OpenJ9.

I highly recommended if you are looking to install Java.

Azul Zulu, Amazon Corretto, SAPMachine

You will find a complete list of OpenJDK builds at the OpenJDK Wikipedia site. Among them are Azul Zulu, Amazon Corretto, as well as SapMachine, to name a few. To oversimplify, it boils down to you having different support options/maintenance guarantees.

But make sure to check out the individual websites to learn about the advantages of each single distribution.

Recommendation

To re-iterate from the beginning, in 2019, unless you have very specific requirements, go get your jdk.zip (.tar.gz/.msi/.pkg) file from https://adoptopenjdk.net or choose a package provided by your OS vendor.

Java Features 8-13

As mentioned at the very beginning of this guide: Essentially all (don’t be picky now) Java 8 language features work in Java 13. The same goes for all other Java versions in between.

In turn, this means that all language features from Java 8 serve as a good Java base knowledge, and everything else (Java 9-13) is pretty much additional features on top of that baseline.

Here’s a quick overview of what specific versions have to offer:

Java 8

Java 8 was a massive release and you can find a list of all features at the Oracle website. There’s two main feature sets I’d like to mention here:

Language Features: Lambdas, etc.

Before Java 8, whenever you wanted to instantiate, for example, a new Runnable, you had to write an anonymous inner class, like so:

Runnable runnable = new Runnable(){

@Override

public void run(){

System.out.println("Hello world !");

}

};With lambdas, the same code looks like this:

Runnable runnable = () -> System.out.println("Hello world two!");You also got method references, repeating annotations, default methods for interfaces, and a few other language features.

Collections & Streams

In Java 8, you also got functional-style operations for collections, also known as the Stream API. A quick example:

List<String> list = Arrays.asList("franz", "ferdinand", "fiel", "vom", "pferd");Now, pre-Java 8, you basically had to write for-loops to do something with that list.

With the Streams API, you can do the following:

list.stream()

.filter(name -> name.startsWith("f"))

.map(String::toUpperCase)

.sorted()

.forEach(System.out::println);Java 9

Java 9 also was a fairly big release, with a couple of additions:

Collections

Collections got a couple of new helper methods to easily construct Lists, Sets, and Maps.

List<String> list = List.of("one", "two", "three");

Set<String> set = Set.of("one", "two", "three");

Map<String, String> map = Map.of("foo", "one", "bar", "two");Streams

Streams got a couple of additions, in the form of takeWhile, dropWhile, and iterate methods.

Stream<String> stream = Stream.iterate("", s -> s + "s")

.takeWhile(s -> s.length() < 10);Optionals

Optionals got the sorely missed ifPresentOrElse method.

user.ifPresentOrElse(this::displayAccount, this::displayLogin);Interfaces

Interfaces got private methods:

public interface MyInterface {

private static void myPrivateMethod(){

System.out.println("Yay, I am private!");

}

}Other Language Features

And a couple of other improvements, like an improved try-with-resources statement or diamond operator extensions.

JShell

Finally, Java got a shell where you can try out simple commands and get immediate results.

% jshell

| Welcome to JShell -- Version 9

| For an introduction type: /help intro

jshell> int x = 10

x ==> 10HTTPClient

Java 9 brought the initial preview version of a new HttpClient. Up until then, Java’s built-in Http support was rather low-level, and you had to fall back on using third-party libraries like Apache HttpClient or OkHttp (which are great libraries, btw!).

With Java 9, Java got its own, modern client — although this is in preview mode, which means that it is subject to change in later Java versions.

Project Jigsaw: Java Modules and Multi-Release Jar Files

Java 9 got the Jigsaw Module System, which somewhat resembles the good old OSGI specification. It is not in the scope of this guide to go into full detail on Jigsaw, but have a look at the previous links to learn more.

Multi-Release .jar files made it possible to have one .jar file which contains different classes for different JVM versions. So, your program can behave differently/have different classes used when run on Java 8 vs. Java 10, for example.

Java 10

There have been a few changes to Java 10, like garbage collection, etc. But the only real change you as a developer will likely see is the introduction of the var keyword, also called local-variable type inference.

Local-Variable Type Inference: var-keyword

// Pre-Java 10

String myName = "Marco";

// With Java 10

var myName = "Marco"Feels Javascript-y, doesn’t it? It is still strongly typed, though, and only applies to variables inside methods (thanks, dpash, for pointing that out again).

Java 11

Java 11 was also a somewhat smaller release, from a developer perspective.

Strings & Files

Strings and files got a couple of new methods (not all listed here):

"Marco".isBlank();

"Mar\nco".lines();

"Marco ".strip();

Path path = Files.writeString(Files.createTempFile("helloworld", ".txt"), "Hi, my name is!");

String s = Files.readString(path);Run Source Files

Starting with Java 10, you can run Java source files without having to compile them first. A step towards scripting.

ubuntu@DESKTOP-168M0IF:~$ java MyScript.javaLocal-Variable Type Inference (var) for Lambda Parameters

The header says it all:

(var firstName, var lastName) -> firstName + lastNameHttpClient

The HttpClient from Java 9 in its final, non-preview version.

Other Goodies

Flight Recorder, No-Op Garbage Collector, Nashorn-Javascript-Engine deprecated, etc.

Java 12

Java 12 got a couple of new features and clean-ups, but the only ones worth mentioning here are Unicode 11 support and a preview of the new switch expression, which you will see covered in the next section.

Java 13

You can find a complete feature list here, but essentially, you are getting Unicode 12.1 support, as well as two new or improved preview features (subject to change in the future):

Switch Expression (Preview)

Switch expressions can now return a value. And you can use a lambda-style syntax for your expressions, without the fall-through/break issues:

Old switch statements looked like this:

switch(status) {

case SUBSCRIBER:

// code block

break;

case FREE_TRIAL:

// code block

break;

default:

// code block

}Whereas with Java 13, switch statements can look like this:

boolean result = switch (status) {

case SUBSCRIBER -> true;

case FREE_TRIAL -> false;

default -> throw new IllegalArgumentException("something is murky!");

};Multiline Strings (Preview)

You can finally do this in Java:

String htmlBeforeJava13 = "<html>\n" +

" <body>\n" +

" <p>Hello, world</p>\n" +

" </body>\n" +

"</html>\n";

String htmlWithJava13 = """

<html>

<body>

<p>Hello, world</p>

</body>

</html>

""";Java 14 and Later

Will be covered here, as soon as they are getting released. Check back soon!

Conclusion

By now, you should have a pretty good overview of a couple of things:

- How to install Java, which version to get, and where to get it from (hint: AdoptOpenJDK).

- What a Java distribution is, which ones exist, and what are the differences.

- What are the differences between specific Java versions.

Feedback, corrections, and random input are always welcome! Simply leave a comment down below.

Thanks for reading!

There’s More Where That Came From

This article originally appeared on www.marcobehler.com/written as part of a series of guides on modern Java programming. To find more guides, visit the website or subscribe to the newsletter to get notified of newly published guides: https://bit.ly/2K0Ao4F.

Acknowledgments

Stephen Colebourne wrote a fantastic article on the different available Java distributions. Thanks, Stephen!

Further Reading

JVM Ecosystem Survey: Why Devs Aren’t Switching to Java 11

When Will Java 11 Replace Java 8 as the Default Java?

credits: https://dzone.com/articles/a-guide-to-java-versions-and-features