Bloom

General concept

A classical Bloom filter is a data structure that enables us to quickly check membership of an element in a set. The filter is highly compact, but allows false positives: it can mistakenly consider an element to be a member of a set (false positive), but it is not permitted to consider an element of a set not to be a member (false negative).

The filter is an array of m bits (also called a signature) that is initially filled with zeros. k different hash functions are chosen that map any element of the set to k bits of the signature. To add an element to the set, we need to set each of these bits in the signature to one. Consequently, if all the bits corresponding to an element are set to one, the element can be a member of the set, but if at least one bit equals zero, the element is not in the set for sure.

In the case of a DBMS, we actually have N separate filters built for each index row. As a rule, several fields are included in the index, and it’s values of these fields that compose the set of elements for each row.

By choosing the length of the signature m, we can find a trade-off between the index size and the probability of false positives. The application area for Bloom index is large, considerably “wide” tables to be queried using filters on each of the fields. This access method, like BRIN, can be regarded as an accelerator of sequential scan: all the matches found by the index must be rechecked with the table, but there is a chance to avoid considering most of the rows at all.

Structure

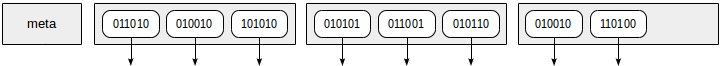

We’ve already discussed signature trees in the context of GiST access method. Unlike these trees, Bloom index is a flat structure. It consists of a metapage followed by regular pages with index rows. Each index row contains a signature and reference to a table row (TID), as schematically shown in the figure.

Creation and choice of parameter values

When creating Bloom index, a total size of the signature (“length”) is specified, as well as the number of bits to be set for each individual field included in the index (“col1″—”col32”):

create index on ... using bloom(...) with (length=..., col1=..., col2=..., ...);

The way to specify the number of bits looks odd: these numbers must be parameters of an operator class rather than the index. The thing is that operator classes cannot be parametrized at present, although work on this is in progress.

The feature (commitfest entry) finally got into PostgreSQL 13.

How can we choose suitable values? The theory states that given the probability p of a filter to return a false positive, the optimal number of signature bits can be estimated as m = −nlog2p / ln 2, where n is the number of fields in the index and the number of bits to be set is k = −log2p.

The signature is stored inside the index as an array of two-byte integer numbers, so the value of m can be safely rounded up to 16.

When choosing the probability p, we need to take into account the size of the index, which will approximately equal (m/8 + 6)N, where N is the number of rows in the table and 6 is the size of the TID pointer in bytes.

A few points to note:

- The probability p of a false positive relates to one filter, therefore, we expect to get Np false positives during table scan (of course, for a query that returns few rows). For example, for a table with one million rows and the probability 0.01, in the query plan, on average, we can expect “Rows Removed by Index Recheck: 10000”.

- Bloom filter is a probabilistic structure. It makes sense to talk of specific numbers only when averaging quite a lot of values, while in each particular case, we can get whatever we can think of.

- The above estimates are based on an idealized mathematical model and a few assumptions. In practice, the result is likely to be worse. So, do not overestimate formulas: they are only a means to choose initial values for future experiments.

- For each field individually, the access method enables us to choose the number of bits to be set. There is a reasonable assumption that actually the optimal number depends on the distribution of the values in the column. To deeper dive, you can read this article (references to other researches are welcome). But reread the previous item first.

Updating

When a new row is inserted in a table, a signature is created: for values of all indexed fields, all their corresponding bits are set to one. In theory, we must have k different hash functions, while in practice, the pseudo-random number generator suffices, whose seed is chosen each time with the help of the only hash function.

A regular Bloom filter does not support deletion of elements, but this is not required for Bloom index: when a table row is deleted, the entire signature is deleted, along with the index row.

As usual, an update consists of deletion of the outdated row version and insertion of the new one (the signature being calculated from scratch).

Scanning

Since the only thing that Bloom filter can do is check membership of an element in a set, the only operation supported by Bloom index is an equality check (like in hash index).

As we already mentioned, Bloom index is flat, so in the course of index access, it is always read successively and entirely. In the course of reading, a bitmap is build, which is then used to access the table.

In a regular index access, it is assumed that few index rows will have to be read and, in addition, they can be soon needed again, therefore, they are stored in a buffer cache. Reading of Bloom index, however, is actually a sequential scan. To prevent from evicting useful information out of the cache, reading is done through a small buffer ring, exactly the same way as for sequential scan of tables.

We should take into account that the more the size of Bloom index, the less attractive it will seem to the planner. This dependency is linear, unlike for tree-like indexes.

Example

Table

Let’s look at Bloom index by example of a big “flights_bi” table from the previous article. To remind you, the size of this table is 4 GB with approximately 30 million rows. Definition of the table:

demo=# \d flights_bi

Table "bookings.flights_bi"

Column | Type | Collation | Nullable | Default

--------------------+--------------------------+-----------+----------+---------

airport_code | character(3) | | |

airport_coord | point | | |

airport_utc_offset | interval | | |

flight_no | character(6) | | |

flight_type | text | | |

scheduled_time | timestamp with time zone | | |

actual_time | timestamp with time zone | | |

aircraft_code | character(3) | | |

seat_no | character varying(4) | | |

fare_conditions | character varying(10) | | |

passenger_id | character varying(20) | | |

passenger_name | text | | |

Let’s first create the extension: although Bloom index is included in a standard delivery starting with version 9.6, it is unavailable by default.

demo=# create extension bloom;

Last time we could index three fields using BRIN (“scheduled_time”, “actual_time”, “airport_utc_offset”). Since Bloom indexes do not depend on the physical order of the data, let’s try to include almost all fields of the table in the index. Let’s however exclude the time fields (“scheduled_time” and “actual_time”): the method only supports comparison for equality, but a query for exact time is hardly interesting to anybody (we could, however, build the index on an expression, rounding the time to a day, but we won’t do this). We will also have to exclude the geographical coordinates of airports (“airport_coord”): looking ahead, the “point” type is not supported.

To choose the parameter values, let’s set the probability of a false positive to 0.01 (having in mind that actually we will get more). The above formulas for n = 9 and N = 30,000,000 give the signature size of 96 bit and suggest setting 7 bits per element. The estimated size of the index is 515 MB (approximately one eighth of the table).

(With the minimal signature size of 16 bits, the formulas promise the index size that is two times smaller, but permit to rely only on the probability of 0.5, which is very poor.)

Operator classes

So, let’s try to create the index.

demo=# create index flights_bi_bloom on flights_bi

using bloom(airport_code, airport_utc_offset, flight_no, flight_type, aircraft_code, seat_no, fare_conditions, passenger_id, passenger_name)

with (length=96, col1=7, col2=7, col3=7, col4=7, col5=7, col6=7, col7=7, col8=7, col9=7);

ERROR: data type character has no default operator class for access method "bloom"

HINT: You must specify an operator class for the index or define a default operator class for the data type.

Unfortunately, the extension provides us with only two operator classes:

demo=# select opcname, opcintype::regtype

from pg_opclass

where opcmethod = (select oid from pg_am where amname = 'bloom')

order by opcintype::regtype::text;

opcname | opcintype

----------+-----------

int4_ops | integer

text_ops | text

(2 rows)

But fortunately, it is pretty easy to create similar classes for other data types as well. An operator class for Bloom access method must contain exactly one operator – equality – and exactly one auxiliary function – hashing. The simplest way to find the needed operators and functions for an arbitrary type is to look into the system catalog for operator classes of “hash” method:

demo=# select distinct

opc.opcintype::regtype::text,

amop.amopopr::regoperator,

ampr.amproc

from pg_am am, pg_opclass opc, pg_amop amop, pg_amproc ampr

where am.amname = 'hash'

and opc.opcmethod = am.oid

and amop.amopfamily = opc.opcfamily

and amop.amoplefttype = opc.opcintype

and amop.amoprighttype = opc.opcintype

and ampr.amprocfamily = opc.opcfamily

and ampr.amproclefttype = opc.opcintype

order by opc.opcintype::regtype::text;

opcintype | amopopr | amproc

-----------+----------------------+--------------

abstime | =(abstime,abstime) | hashint4

aclitem | =(aclitem,aclitem) | hash_aclitem

anyarray | =(anyarray,anyarray) | hash_array

anyenum | =(anyenum,anyenum) | hashenum

anyrange | =(anyrange,anyrange) | hash_range

...

We will create two missing classes using this information:

demo=# CREATE OPERATOR CLASS character_ops

DEFAULT FOR TYPE character USING bloom AS

OPERATOR 1 =(character,character),

FUNCTION 1 hashbpchar;

demo=# CREATE OPERATOR CLASS interval_ops

DEFAULT FOR TYPE interval USING bloom AS

OPERATOR 1 =(interval,interval),

FUNCTION 1 interval_hash;

A hash function is not defined for points (“point” type), and it is for this reason that we cannot build Bloom index on such a field (just like we cannot perform a hash join on fields of this type).

Trying again:

demo=# create index flights_bi_bloom on flights_bi

using bloom(airport_code, airport_utc_offset, flight_no, flight_type, aircraft_code, seat_no, fare_conditions, passenger_id, passenger_name)

with (length=96, col1=7, col2=7, col3=7, col4=7, col5=7, col6=7, col7=7, col8=7, col9=7);

CREATE INDEX

The size of the index is 526 MB, which is somewhat larger than expected. This is because the formula does not take page overhead into account.

demo=# select pg_size_pretty(pg_total_relation_size('flights_bi_bloom'));

pg_size_pretty

----------------

526 MB

(1 row)

Queries

We can now perform search using various criteria, and the index will support it.

As we already mentioned, Bloom filter is a probabilistic structure, therefore, the efficiency highly depends on each particular case. For example, let’s look at the rows related to two passengers, Miroslav Sidorov:

demo=# explain(costs off,analyze)

select * from flights_bi where passenger_name='MIROSLAV SIDOROV';

QUERY PLAN

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Bitmap Heap Scan on flights_bi (actual time=2639.010..3010.692 rows=2 loops=1)

Recheck Cond: (passenger_name = 'MIROSLAV SIDOROV'::text)

Rows Removed by Index Recheck: 38562

Heap Blocks: exact=21726

-> Bitmap Index Scan on flights_bi_bloom (actual time=1065.191..1065.191 rows=38564 loops=1)

Index Cond: (passenger_name = 'MIROSLAV SIDOROV'::text)

Planning time: 0.109 ms

Execution time: 3010.736 ms

and Marfa Soloveva:

demo=# explain(costs off,analyze)

select * from flights_bi where passenger_name='MARFA SOLOVEVA';

QUERY PLAN

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Bitmap Heap Scan on flights_bi (actual time=9980.884..10142.684 rows=2 loops=1)

Recheck Cond: (passenger_name = 'MARFA SOLOVEVA'::text)

Rows Removed by Index Recheck: 3950168

Heap Blocks: exact=45757 lossy=67332

-> Bitmap Index Scan on flights_bi_bloom (actual time=1037.588..1037.588 rows=212972 loops=1)

Index Cond: (passenger_name = 'MARFA SOLOVEVA'::text)

Planning time: 0.157 ms

Execution time: 10142.730 ms

In one case, the filter allowed only 40 thousand false positives and as much as 4 million of them in the other one (“Rows Removed by Index Recheck”). The execution times of the queries differ accordingly.

And the following are the results of searching the same rows by the passenger ID rather than name. Miroslav:

demo=# explain(costs off,analyze)

demo-# select * from flights_bi where passenger_id='5864 006033';

QUERY PLAN

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Bitmap Heap Scan on flights_bi (actual time=13747.305..16907.387 rows=2 loops=1)

Recheck Cond: ((passenger_id)::text = '5864 006033'::text)

Rows Removed by Index Recheck: 9620258

Heap Blocks: exact=50510 lossy=165722

-> Bitmap Index Scan on flights_bi_bloom (actual time=937.202..937.202 rows=426474 loops=1)

Index Cond: ((passenger_id)::text = '5864 006033'::text)

Planning time: 0.110 ms

Execution time: 16907.423 ms

And Marfa:

demo=# explain(costs off,analyze)

select * from flights_bi where passenger_id='2461 559238';

QUERY PLAN

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Bitmap Heap Scan on flights_bi (actual time=3881.615..3934.481 rows=2 loops=1)

Recheck Cond: ((passenger_id)::text = '2461 559238'::text)

Rows Removed by Index Recheck: 30669

Heap Blocks: exact=27513

-> Bitmap Index Scan on flights_bi_bloom (actual time=1084.391..1084.391 rows=30671 loops=1)

Index Cond: ((passenger_id)::text = '2461 559238'::text)

Planning time: 0.120 ms

Execution time: 3934.517 ms

The efficiencies differ much again, and this time Marfa was more lucky.

Note that search by two fields simultaneously will be done much more efficiently since the probability of a false positive p turns into p2:

demo=# explain(costs off,analyze)

select * from flights_bi

where passenger_name='MIROSLAV SIDOROV'

and passenger_id='5864 006033';

QUERY PLAN

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Bitmap Heap Scan on flights_bi (actual time=872.593..877.915 rows=2 loops=1)

Recheck Cond: (((passenger_id)::text = '5864 006033'::text)

AND (passenger_name = 'MIROSLAV SIDOROV'::text))

Rows Removed by Index Recheck: 357

Heap Blocks: exact=356

-> Bitmap Index Scan on flights_bi_bloom (actual time=832.041..832.041 rows=359 loops=1)

Index Cond: (((passenger_id)::text = '5864 006033'::text)

AND (passenger_name = 'MIROSLAV SIDOROV'::text))

Planning time: 0.524 ms

Execution time: 877.967 ms

However, search with Boolean “or” is not supported at all; this is a limitation of a planner rather than of the access method. Of course, an option remains to read the index twice, build two bitmaps, and join them, but this is most likely too costly for this plan to be chosen.

Comparison with BRIN and Hash

Application areas of Bloom and BRIN indexes obviously intersect. These are large tables for which it is desirable to ensure search by different fields, the search accuracy being sacrificed to compactness.

BRIN indexes are more compact (say, by up to dozens of megabytes in our example) and can support search by range, but have a strong limitation related to physical ordering of the data in a file. Bloom indexes are larger (hundreds of megabytes), but have no limitations except an availability of a suitable hash function.

Like Bloom indexes, hash indexes support the only operation of equality check. Hash index ensures the search accuracy that is inaccessible for Bloom, but the index size is way larger (in our example, a gigabyte for only one field, and hash index cannot be created on several fields).

Properties

As usual, let’s look at the properties of Bloom (queries have already been provided).

The following are the properties of the access method:

amname | name | pg_indexam_has_property

--------+---------------+-------------------------

bloom | can_order | f

bloom | can_unique | f

bloom | can_multi_col | t

bloom | can_exclude | f

Evidently, the access method enables us to build an index on several columns. It hardly makes sense to create Bloom index on one column.

The following index-layer properties are available:

name | pg_index_has_property

---------------+-----------------------

clusterable | f

index_scan | f

bitmap_scan | t

backward_scan | f

The only available scan technique is bitmap scan. Since the index is always scanned entirely, it does not make sense to implement a regular index access that returns rows TID by TID.

name | pg_index_column_has_property

--------------------+------------------------------

asc | f

desc | f

nulls_first | f

nulls_last | f

orderable | f

distance_orderable | f

returnable | f

search_array | f

search_nulls | f

Only dashes are here; the method cannot even manipulate NULLs.

And finally:

It’s not impossible that this series of articles will be continued in future, when new index types of interest appear, but it’s time to stop now.

I’d like to express appreciation to my colleagues from Postgres Professional (some of them are the authors of many access methods discussed) for reading the drafts and providing their comments. And I’m, certainly, grateful to you for your patience and valuable comments. Your attention encouraged me to reach this point. Thank you!

Ref: https://postgrespro.com/blog/pgsql/5967832